What drives computers to obsolescence?

2025-04-19

It was 2021 when Microsoft released the next major revision of the ubiquitous Windows operating system, and along with it came the usual requirement for users to have newer hardware to upgrade. This time around, computers older than 2018 were destined for purgatory just 3 short years after they came to exist. Fast forward to today, and the holdouts who still run Windows 10 are now facing retribution this October with Microsoft's final warning before they leave those computers in the dust, unsecured against viruses and exploits [1]. Because of this, it's likely that an astronomically large number of electronics will be thrown away rather than used for the years to come. This brings to light two ongoing issues: 1) the creation of electronic waste, and 2) the need for people to purchase expensive machines despite already owning capable machines.

Some might disregard the second point on the basis that people don't want to use old devices; after all, anyone who's been stuck with a 5-to-10 year old laptop would know that they're typically quite slow, oftentimes glitchy, and more often than not there are some applications which just refuse to run on dated computers. These issues are especially prevalent in those small mobile computers we call phones. But what if computers didn't degrade like this with age? Is it possible to make a computer run effectively through a lifetime of, say, over 10 years? And if so, what are the implications?

In order to determine the practicality of longer-lasting devices, one must question the reason why they degrade in the first place. Part of the issue is that hardware simply falls apart; given enough time, monitors can develop dead pixels and an off-white tint, hard drives can malfunction and effectively self-destruct, and batteries lose their ability to hold a charge. On the other hand, monitors have improved with time and rarely defect, advancements in SSD hard drive technology has notably reduced the chance of failure, and batteries are simple to replace for a low price, not to mention the laptop I've designed this website on and wrote this post with is 9 years old and still going without ever having upgrades nor repairs. Hell, the battery is still able to hold a charge for a good 5 hours of active use!

My laptop from 2016. Taken 2025-04-15.

My laptop from 2016. Taken 2025-04-15.

So it's not hardware?

Notwithstanding intermittent and occasional manufacturing defects and faulty components that require maintenance and repairs, the physical limitations of hardware isn't what prevents computers from a 10-year or longer life cycle, thus the problem must lie somewhere within the software. As a result of this finding, it's easy to blame innovation as the root cause; it's easy to say that the next big thing needs more powerful machines, that modern expectations for computers necessitate power-hungry AI applications and whatnot, and that old devices just won't make the cut.

There is a degree of truth to these statements; for reference, the 2005 Nintendo DS gaming console had a clock speed of 67 megahertz (meaning it can run about 67 million operations per second depending on how you count), while an average laptop these days can reach into the thousands of megahertz. Go back a bit further to the 1980s and you might find, just as long-time programmer James Hague did in his 2008 post on the matter, that something like a simple spellchecker could take someone months to create due to the dedication required to make it fast enough to run in a reasonable amount of time, whereas these days a spellchecker could be made in a matter of minutes by a programmer with a bit of insight [2].

The point is, there has been a long-standing trend of advancements in computer technology which will likely continue for time to come. It's realistic to think that the technology of today may very well be obsolete compared to hardware available a decade from now. From that, it's possible to conclude that in the future, the computers we have now will not satisfy the needs of users and thus we will all require new ones sooner or later.

The issue that lies in these comparisons is that they are relative. Consider an absolute perspective: if the computers of today can adequately fulfill the needs of those who use them, then surely they would be capable of fulfilling those same needs in a year, or two years, or five years, and so on and so forth until the device eventually accumulates a decade and change's worth of physical wear and tear to the point it no longer functions. In other words, the existence of faster computers doesn't make standard computers worse than they are now, or at least it wouldn't make much sense if it did...

In practice, I think many, including myself, can attest to the fact that machines do tend to slow down with time; an iPhone, for example, is hardly usable beyond texting after six or so years; apps will take an eternity to load compared to the day the phone was bought, and good luck loading a large website before the connection times out. So what gives?

Insight from the past

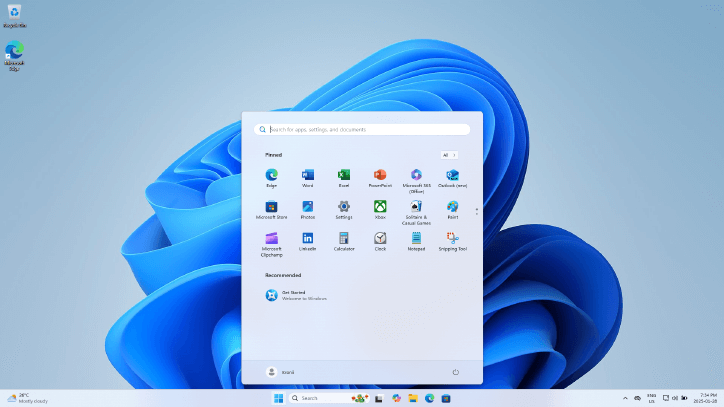

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Windows_11_Desktop.png

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Windows_11_Desktop.png

Perhaps a trip through time will shed some light on the issue. Above is a screenshot of a Windows 11 home screen, courtesy of Wikipedia and Microsoft. It's quite empty really; a web browser in the corner, standard office tools installed, an app store, system utilities. Throw in some games and professional software and I think that covers most of what people use laptops and desktops for.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Windows_8_Desktop.png

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Windows_8_Desktop.png

Windows 8. Remarkably similar to its successors, and yet it takes just a quarter of the memory and storage to install in comparison.

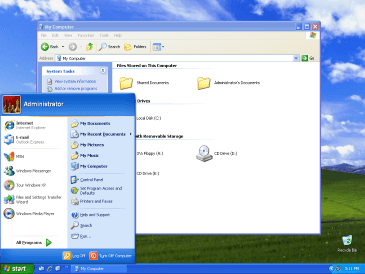

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Windows_XP_Luna.png

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Windows_XP_Luna.png

2001: the introduction of Windows XP. A mere 64 MiB of RAM can get this system up and running--less than 1.6% of the memory required to boot up Windows 11. As for storage, XP only needs 1.5 GB, under 2.4% of what Windows 11 mandates.

The color scheme may look less appealing a couple decades after its release, but that's nothing that a designer couldn't have fixed up. The real question is if 24 years ago a desktop home screen required such a comparatively small amount of computing resources, what is all of that extra hardware, extra memory, and extra storage being used for in Windows 11's home screen?

Some of it can be chalked up to new features; it's not like Copilot existed back in the era of Windows XP, but then again most of the energy used by that kind of AI is done on servers rather than personal machines. It can be argued that smoother animations contribute to the huge jump in resource usage, but disabling animations only results in a small improvement.

A silver lining?

Let's consider another operating system, one that is more independent of megacorporations: Linux. This open-source system is highly configurable, and consequently the hardware requirements can vary quite wildly depending on said configuration and the distribution it's a part of. Some stripped-down Linux systems are able to run on as few resources as Windows XP or even less, although in my experience the commonly recommended Linux distributions with high-quality design typically have hardware requirements closer to that of Windows 8. Either way, it needs just a small fraction of the computing ability relative to Windows 11, despite being fully capable of performing the same tasks.

There is no technical limitation to the performance of Windows (and subsequently the performance of any retail computer with Windows preinstalled), so why is it so wasteful?

Is it just the inherent difficulty in optimizing software? Making high-speed, low-footprint software requires a balance between working on functionality and optimizing the code; it may be possible to make a spellchecker that runs on kilobytes of memory, but if a few megabytes can be spared the problem of writing the software is simplified tremendously. Then again, consider that distributions of Linux that do not emphasize performance are still able to outperform modern versions of Windows, so the source of the issue must be something else.

Maybe it's just a lack of awareness amongst software developers. A questionnaire directed by Włodzimierz Wysocki found that few developers give thought to the energy consumption of the programs they write, and even fewer know methods of reducing such waste [3].

Related to both of the previous points is a lack of prioritization; even if a programmer is able to speed up their programs, that means dedicating time to both learning how and experimenting with improvements, time which could have otherwise been dedicated to pushing new features and working on other projects. It could just be a case as described by Drew DeVault, where accumulated complexity in a program can make optimizing an incredibly time-consuming process [4]. When employers are involved, the problem is only exacerbated: what motive does an employer have to allocate their employees' time to optimizing software?

A check with reality

Consumer culture tells us to buy new devices when a piece of software is too slow on existing devices, and this fuels a tendency in the general population to blame hardware rather than software as the cause of underperformance. I've seen it play out again and again: gamers purchasing the latest high-end graphics processors because the next big game needs it, or people grabbing a new laptop for the usual web browsing, document editing and email combo. But do games really need that much power? Do basic office suite applications really need the latest and greatest in processor technology? I'm inclined to say no.

I've seen professional games skyrocket in size over the years, from installations as low as 16 MB to as much as 160 GB--ten thousand times as much storage.

I've seen obscure, open-source document editors that run swiftly on budget electronics of the past and popular commercial document editors that take 10 minutes just to start up on high-end, multi-thousand dollar models of the same year.

The balance of optimizing has been lost in mainstream software, applications, games. The consequence is an ever-growing pile of electronic waste, one that enables hardware companies to thrive by increasing demand for the latest models; to draw upon the words of Andrew Kelley, lead programmer of the Zig programming language and toolchain, it's how profits keep rising; "it's how the line goes up" [5].

Computers are capable of reaching life cycles of 10 years and beyond, it's just a matter of choosing the right software. It may be obscure, but with the flourishing of the open-source software community that is unaffected by the motives of commercial software developers, efficient alternatives to almost every program exists; you just need to find them.

References

- Microsoft, "Your Windows 10 end of support checklist," 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/learning-center/windows-10-end-of-support-checklist [Accessed Apr. 19, 2025].

- J. Hague, "A Spellchecker Used to Be a Major Feat of Software Engineering," 2008. [Online]. Available: https://prog21.dadgum.com/29.html [Accessed Apr. 19, 2025].

- W. Wysocki, “Why Don’t Software Companies Care About Software Energy Efficiency? A Survey of Software Industry Developers.” 2024. Procedia Computer Science 246 (C): 5054–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2024.09.589.

- D. DeVault, "Simple, correct, fast: in that order," 2018. [Online]. Available: https://drewdevault.com/2018/07/09/Simple-correct-fast.html [Accessed Apr. 19, 2025].

- A. Kelley, "Why We Can't Have Nice Software," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://andrewkelley.me/post/why-we-cant-have-nice-software.html [Accessed Apr. 19, 2025]